Christian Athletes and the Sermon on the Mount

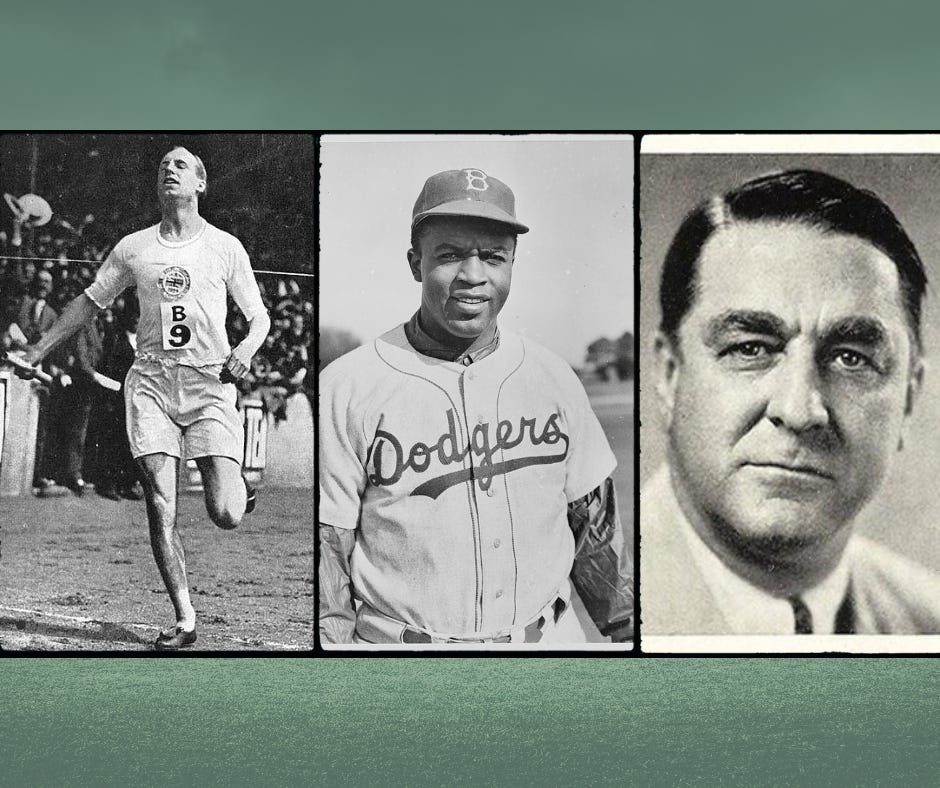

Looking back at Eric Liddell, Jackie Robinson, Branch Rickey, and other Christian athletes who have been shaped and inspired by the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled….

I was in my early 20s the first time I was truly drawn in and captivated by the Sermon on the Mount.

As a pastor’s kid who had attended a Bible college, I knew all the verses and the basic outline. But I had not really thought of it in a comprehensive way.

Then I went through a study of the Sermon on the Mount with the pastor of a new church I was attending. It was one of the most transformative experiences in my development as a Christian. I saw more clearly how Jesus’s teachings turned worldly values and priorities upside down, calling Christians to a different kingdom— a different way of living right here and now.

I’ve been reflecting on that experience this week because my church is starting its own deep dive into the Sermon on the Mount (and so is a podcast I follow, the Bible Project).

This means, of course, that I’ve also been thinking about the sports angle.

For some, the Sermon on the Mount seems to clash with the competitive ethos of sports. How can Christian athletes square Jesus’s command to “turn the other cheek” with the inherent need in sports to face your opponent and refuse to back down?

I think it’s good for Christian athletes and coaches to wrestle with these questions and tensions. But it’s also good to know that there are Christian athletes in the past who have thought deeply about the meaning of the Sermon on the Mount.

That’s what I’d like to focus on as we kick off the start of a new year.

The interpretations of the individuals below might not match my own. But they have all approached the text as a challenge requiring a response, rather than something to explain away or ignore.

Christians across the United States, I think, would do well to sit with Jesus’s teachings from the Sermon on the Mount in a similar way this year.

Eric Liddell

Eric Liddell is most famous for his performance at the 1924 Olympics. The Scottish sprinter, a contender to win the 100 meters, withdrew from the event because the heats were held on a Sunday. And Sunday, Liddell believed, was supposed to be a day of rest and worship. Instead, he raced in the 400 meters, an event with which he was less familiar—and in which he won the gold.

While Liddell was a hero in the United Kingdom, it was not until the 1981 film, Chariots of Fire, that his Olympic story truly caught on in the United States. “I believe God made me for a purpose,” Liddell says in a famous (and fictionalized) line from the movie, “but he also made me fast! And when I run I feel his pleasure.”

Still, even in the 1920s, his willingness to prioritize Christian convictions over the glory of a gold medal made him a model Christian athlete for many. Liddell’s career after the Olympics also won praise from his Christian fans: he became a missionary in China, where he continued to develop and grow in his faith (and occasionally participate in sports).1

The Sermon on the Mount loomed large in Liddell’s spiritual development, serving as a key part of his personal creed. “I believe in the Sermon on the Mount and in its way of life,” he wrote in The Disciplines of the Christian Life, “and I intend, God helping me, to embody it in my life.”

Influenced by Methodist missionary E. Stanley Jones’s The Christ on the Mount: A Working Philosophy (1931), Liddell believed the Sermon on the Mount presented Christians with a vision of the type of person they should become. By surrendering selfish desires, trusting God, and practicing the disciplines of faith, love, and obedience, Christians could grow into people who exemplified the Beatitudes.

“Read the Sermon on the Mount over and over again. Ponder its meaning; apply it to your daily life,” Liddell encouraged. “Do not hedge or try to explain it away. Do not dilute its meaning but face its challenge. Discover—or rediscover—it as a practical way of living.”

Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson

Liddell died in a prison camp in 1945, right at the end of World War II. A few months later, across the Pacific Ocean in North America, the most famous example of the Sermon on the Mount within sports was put into practice.

It started in the office of Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey as he met with Jackie Robinson. During that historic August day, Major League Baseball’s color line would be broken. But first, there was a one-man show put on by Rickey.

The story has been told plenty of times: How Branch Rickey worked himself into a lather acting out different scenarios and situations Robinson might find himself in, asking if the star athlete would be able to withstand the racist abuse sure to come his way.

According to Rickey’s biographer Lee Lowenfish, in the middle of this scene, Rickey paused and “pulled out of his desk drawer a heavily marked passage from one of his favorite books, Giovanni Papini's The Life of Christ.”

Translated from Italian and published in English in 1923, Papini’s biography of Jesus had been a best-seller in the 1920s. Rickey read Robinson a section in which Papini discussed the “revolutionary” teachings of nonresistance found in the Sermon on the Mount: “Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth: But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil: But whosoever shall smite thee on thy cheek turn to him the other also.”

According to Rickey, “it was not the philosophy of Papini that hit me so hard.” Instead, it was the “assiduous acquaintanceship with the Christ" that Papini’s book conveyed. Papini wanted to “make Christ more living…to make us feel Him as actually and eternally present in our lives.” That was Rickey’s focus as well.

Unlike Liddell, who saw the Sermon on the Mount as a creed to live by, Rickey saw it as an expression of the dynamic personality of Jesus. It inspired more than instructed. “His Sermon on the Mount really makes me wish to be a good man—a better man,” Rickey wrote.

As for Robinson, his response was more layered and complex. He was a Methodist, like Rickey. He sought to follow Jesus, like Rickey.2 But “turning the other cheek” in his context meant ignoring racist taunts and actions, a burden that went against his fiercely competitive personality and sense of justice. It was also bound up with racial paternalism, in which Black players were expected to meet a special standard of perfection on and off the field in order to be accepted.

"Could I turn the other cheek? I didn't know how I would do it,” Robinson wrote in his autobiography. “Yet I knew that I must. I had to do it for so many reasons.”

Over the years, the “turn the other cheek” narrative has sometimes been exaggerated and mythologized. And yet, it reflects a part of the story that Robinson himself embraced, and a compelling—and costly—example of the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount lived out in the real world.3

Martin Luther King, Jr. put it well when he honored Robinson in 1962:

“Jackie Robinson incessantly raises questions to sear America’s conscience,” King wrote. “Back in the days when integration wasn’t fashionable, he underwent the trauma and the humiliation and the loneliness which comes with being a pilgrim walking toward the lonesome byways toward the road of Freedom. He was a sit-inner before the sit-ins, a freedom rider before the freedom rides.”

Bruce Bickel and the Fellowship of Christian Athletes

Eric Liddell, Jackie Robinson, and Branch Rickey may have been Christian athletes. But for most of their careers, they were not part of an organized Christian athlete community—no such thing existed.

In 1954, that changed with the formation of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. Branch Rickey was a founding member of the group. And by the 1970s, the movement had expanded to include multiple sports ministries, forming an evangelical Christian subculture within sports.

As this subculture matured, sports ministries developed new teachings and trainings to help Christian athletes and coaches live out their faith within sports. They asked: What does it mean to be a Christian athlete? How are Christian athletes different from the world around them? What are the distinctive ways Christian athletes are called to live?

For FCA staff member Bruce Bickel, working in Chicago in the 1970s, the Sermon on the Mount offered an important guide. He noticed a contrast between the platform-based evangelism of sports ministries, which often associated celebrity and fame with Christian witness, and the teachings of Jesus. “Being in the public eye as an athlete or coach is not necessarily a sign of successful Christian living,” he came to believe, “nor does it necessarily contribute to the Kingdom of God (read Matthew 6).”

Bickel developed a Bible study on these themes for the athletes he worked with, including the Chicago Bears. And he wrote about his ideas in the FCA’s magazine.

“The message of the Gospel within the athletic community is only as powerful as Christian athletes and coaches present an alternative,” he explained. And this alternative was “the style of life as lived by Jesus and taught by him in the Sermon on the Mount.”

By learning to live the “alternative life” modeled and taught by Jesus, Bickel suggested, Christian athletes could provide an authentic, mature, and credible witness to teammates, coaches, and fans.

Bickel moved on from FCA in the 1980s. But in the decades since, other sports ministry leaders have followed his lead in trying to apply the teachings of the Sermon on the Mount to the world of sports.

What do you think? Where have you seen Christian athletes and coaches living in ways that reflect Jesus’s teachings in Matthew 5-7? What are the unique challenges and opportunities Christians in sports might face?

I’d love to hear your thoughts, so drop me an email or a note in the comments.

In the meantime, as my church community moves through the Sermon on the Mount this year, I’ll be considering anew what it might have to say about sports.

For a great book on Liddell’s life, check out Duncan Hamilton’s For the Glory: Eric Liddell’s Journey from Olympic Champion to Modern Martyr. You can read my review of the book here.

For a discussion of Jackie Robinson’s Christian faith, you can read my book review essay for Religion & Politics here.

For an example of a critical assessment of the “turn the other cheek” narrative, see Carmen Nanko-Fernández, “Turning Those Others’ Cheeks: Racial Martyrdom and the Re-Integration of Major League Baseball,” in Gods, Games, & Globalization: New Perspectives on Religion and Sport eds. Rebecca Alpert and Arthur Remillard (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2019), 239-262.